Surveillance Video Becomes a Tool for Studying Customers

|

Software mines security footage to help business owners see what people do once they’re inside the store. The huge success of online shopping and advertising—led by giants like Amazon and Google—is in no small part thanks to software that logs when you visit Web pages and what you click on. Startup Prism Skylabs offers brick-and-mortar businesses the equivalent—counting, logging, and tracking people in a store, coffee shop, or gym with software that works with video from security cameras. |

|

|

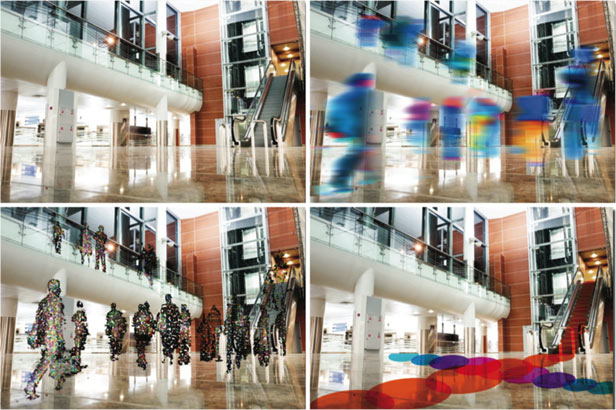

“There’s a lot of wonderful information locked up in video, and 40 million security cameras in the U.S. collecting it, but it’s data that’s not been available,” says Steve Russell, cofounder and CEO of Prism, based in San Francisco. “We want to free up that information.” Prism’s software can count people that come into a business, measure the length of the line at checkout, and produce static or animated visualizations showing how people moved around a store. It is designed so that it cannot identify or track individuals. One national wireless carrier is already using Prism’s technology to generate heat maps of where visitors go in their showrooms, to compare the level of interest in different devices—valuable data to them and to the device makers. Prism’s software can also be used to turn security footage into a live version of Google’s Street View, says Ron Palmeri, Prism’s president and other cofounder. “We give the ability to go beyond the facades of businesses and show you the inside and even how busy it is, using very effectively privacy-protected imagery.” That imagery can show people blurred into anonymous ghosts, in what Russell calls “Predator vision” (a pixelated image), or have people disappear altogether to be replaced with a “heat map,” on which colors signal the density of people. One gym in San Francisco trialing the technology plans to use it to show customers a live view of how busy it is. Although security cameras are typically low quality, Prism uses computational photography techniques to combine multiple frames to produce images with higher quality and resolution than the original video. “We can remove the ugly, grainy quality of surveillance footage,” says Russell. Prism’s software is designed to be used with existing security cameras. Software installed on a computer linked to the cameras digests the raw video into a compressed form that is sent to cloud servers, where Prism’s software does the hard work. It sends back the visualizations, statistics, and other data it extracts to a PC, smart phone, or tablet. Since surveillance cameras are static, Prism’s software can work out which parts of a scene are fixed in place, such as walls, flooring, and furniture. Anything that moves against that background is clipped out and subjected to further processing. Russell hints that he hopes to eventually offer more sophisticated analysis by taking advantage of emerging computational photography techniques—for example, Lytro’s light field cameras, which produce images that can be refocused after they have been taken. Video processing software is most often used for security purposes today, says Jon Cropley, who researches video surveillance technology at IMS Research. Such software, for example, can alert security staff if someone climbs over a wall. Other companies offer software that can count the length of a checkout line and summon staff if a new register needs to be opened. But Cropley says Prism’s technology stands apart. “The established way of doing video content analysis requires dedicated hardware and cameras, and Prism doesn’t,” he says. “Their technology is based on the premise that security cameras are already installed in so many places.” Cropley adds that using surveillance footage to give customers a preview of what a store or restaurant looks like inside is also a promising, if untested, idea. “A lot of customers use still images to see what a place is like, but if you want a real impression, you really want to see live video.” Prism’s technology could also help companies like Groupon and Google shake up advertising for brick-and-mortar businesses. Online, it is easy to track whether people who click on an ad buy anything or become regular customers. Offline, many small businesses have struggled to find if offering big discounts via Groupon, for example, leads to more than a temporary surge of customers who will never come back. “We can help them understand how what’s happening in the store is related to online concepts like Yelp reviews or online deals,” says Russell. “It’s like Google Analytics for the real world,” he adds, referring to the most widely used software for tracking and logging how people use websites. Prism can also draw on online sources of data such as Facebook or Foursquare check-ins to correlate online promotions or deals with real-world activity. This could tell a company if an online coupon led to more visitors to a store. |

|

| Source : http://www.technologyreview.in/computing/39552/ | |